[For the first two installments, go here and here.]

[For the first two installments, go here and here.]

My primary motivation for visiting Cuba had everything to do with art. Naturally, I’ve seen the Cuban art that makes it to the US, but what of the art that doesn’t, which is of course most of it?

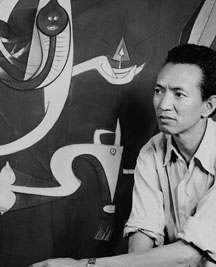

I love surrealism and am a big fan of Wifredo Lam, one of the most influential of the Cuban surrealists. I was hoping to see if there were any modern day artists influenced by Lam and to see generally what indigenous Cuban art is like.

Art culture in any country is always more complex than you expect it to be and Cuba is no exception. Perhaps the best way to get an impression of a culture’s art is to see where it comes from.

Cuba’s government has gone through periods when it more stridently sought to suppress and punish viewpoints it deemed to violate the “spirit of the revolution,” such as those illuminating poverty, racism or any other societal ill that the revolution supposedly cured. Very recently – and I mean within the last few years – artists seem to be freer to communicate any message that is not blatantly critical of the current government and deified leaders of the revolution. There’s no doubt that certain things cannot be said (at least not directly), but this is not Soviet Communism or Nazi Fascism seeking to propagandize art and bend it to meet its own political ends.

Artists should be able to say whatever they want through their art and no subject matter should be off limits; yet, being able to say anything does not mean that you have anything meaningful to say. Political art is often bad art. When it is good it takes tremendous skill and is often conveyed through subtle messaging, which I think is what is happening in Cuba. Perhaps most revealing is what I did not see: contemporary art obviously celebrating the Cuban state or the revolution or communist ideals.

At the risk of sounding crass, money is motivating Cuban art right now: both the lack of it and the need for it. Cuban artists’ innovation in use and reuse of materials- newspapers as canvas; homemade paint; electrical wires, pipe and old tools for sculpture – is a necessity in a country where no one can live on his/her official state income.

And because state incomes are grossly inadequate, many of those who are in a position to benefit from opportunities to make a living in some private endeavor due to the economic reforms of the last few years do so. Tourism in particular is allowing some to raise their standard of living through tips and small private enterprises.

As is the case with most tourist-based economies, private businesses that cater to tourists – including those in the arts – are giving the people what they want. Tourist art is everywhere with its cartoonish figures and saturated colors, and it seems you have to look a little harder than in years past to find art that is more personal. Almost all artists do it: they make art they know will sell and they also make the art that they are driven to make as an artist. One funds the other.

Walking through Old Havana, you can search out the small, private ateliers from which many artists sell their work. There are no signs; just stick your head through the open doors along the street to see what’s inside. For me, this is what art is all about. It’s Havana’s version of open studios.

Artists have always benefitted from collective/communal approaches to making and presenting their art, and, as you would expect, Cuban artists are finding support and community through collective organizations. I visited one such collective with a few friends from the group: Taller Experimental de Gráfica is an artists collective and center for all things related to the art of printmaking (for more photos, go here). This was one of the highlights of the trip (if you are reading this, Connie, thank you for taking me along).

Previously a country club under Batista and one of the premier art universities in Cuba, the Instituto Superior de Artes (ISA) is a work of art in its own right with its intricate brick-work snaking through a campus dotted with large domed studio spaces.

Designed by Ricardo Porro, Roberto Gottardi and Vittorio Garatti, the design proved too controversial for Castro’s Cuba and its Soviet supporters who favored the bland functionalist style (to read more, go here). Despite such Cold-War-era philistinism, the campus has been embraced by Cuba and the world over the last 10-15 years being recognized as a national monument by the Cuban government in 2010 and is currently being considered for World Heritage Site status.

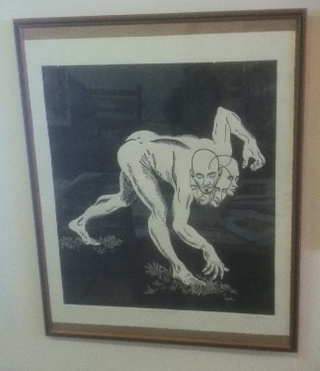

Most of the art felt experimental and unfinished, which is as it should be among student artists, but vibrant. It’s that palpable energy of discovery that always makes me miss the academic environment. We were able to interact with the students and professors, one of whom – Aliosky Garcia – creates some of the most striking woodcut pieces I’ve ever seen. One part folk art and one part surrealist nightmare, the prints entice and repel, balance the beautiful with the grotesque. And you can’t look away; nor do you want to.

On our last night, we were invited into the studio-gallery of two artists (and brothers) for our farewell dinner and reception. The art of both uses existing imagery to make social and political statements about Cuban culture and history, especially in relation to the U.S.

My favorite pieces were Kelvin Lopez’s cigar boxes. Like insects in amber, the layers of resin rise within the box and suspend carefully chosen images from history and pop culture to give the work a three-dimensional quality.

Reminiscent of Rauschenberg, the interiors reveal collages of symbols with meaning beyond the confines of their wooden walls. It’s the cigar box as a symbol of all things Cuban trying to quarantine the pernicious cultural influences of a decadent capitalist world. But what is most striking about the work is how fragile the boxes are and, therefore, how precarious the preservation of Cuban identity. And for Americans, the pieces also serve as a sly jab at the embargo.

For more of Kelvin’s art, go here. For his brother, Kadir, go here.

Another highlight of the trip was having the pleasure of meeting one of the most significant contemporary Cuban artists: Rigoberto Mena. An abstract artist and a lovely and patient man, he came to our hotel lounge (thanks to an invitation from one of our group, Linda M.) and showed us images of his home, family, and work on his iPad.

For more images of Mena’s work, check out his website.

(To be continued)

Hi. Your blog is so fascinating! Especially given the research I’m doing. As a lifelong educator and someone who has been to Cuba many times, I am of course attracted to this article. I’d like to talk to you about a particular photo you have in the article, the ISA Campus, for possible use in my forthcoming book about Education in Cuba. I would greatly appreciate you contacting me to discuss this. Thank you for your time!